Protect Teacher Time At All Costs: A Logic Model to Retain Teachers & Accelerate Learning

We need to accelerate learning for marginalized students. To do that well, we need to rethink how we support teachers.

Despite the headlines, a few new studies suggest that staff shortages may not be our biggest barrier as students return to school this fall. Instead, the rate of learning recovery post pandemic is threatening to perpetuate persistent (and potentially widened) inequities among students along lines of race and class. While it’s impossible to deny the connection between the ability to attract and retain high quality teachers and student achievement, the data is concerning.

Recently released data from NWEA reports that while learning gains are being made post-pandemic, if the rate of learning stays the same, it will take 4-8th graders more than 5 years to close the gap of what they’ve lost. Specifically, NWEA notes:

“In most cases these recovery timelines extend past spending deadlines for federal recovery funds, and for some students, full recovery would not be attainable before the end of high school.”

Test scores as reflected by academic gains in the school year 2021-22 are rebounding and are close to pre-pandemic rates (meaning students are close to learning a years worth of content within an academic year).

However, given disparities in learning loss, students in low-poverty schools will recover faster than in high poverty schools.

Concern that “one size fits all” approaches to interventions will do more to reinforce pre-pandemic educational inequities, rather than eradicating them; there is a call to action to “right size” intervention and recovery efforts so they meet the varying contexts and needs of schools.

The report warns, “Truly achieving recovery requires above-average growth—and for some students, that growth will have to be well above average. Otherwise, widened education inequities will be the lasting legacy of this pandemic.”

So, how might this relate to school staffing? The Hechinger Report and RAND both point to potentially misleading headlines related to school staffing; while teacher attrition has increased, schools are also hiring more teachers and support staff in a race to expense federal funds and make up for learning lost in the pandemic. And demand is outpacing supply.

Bus drivers, substitutes, special education teachers, and English language learner teachers are, in fact, in short supply. Their absence can threaten to overburden educators who are returning to the classroom this fall.

Additionally, data from Missouri (where we are headquartered) speaks to enrollment in teacher preparation programs having declined 25% over the last decade, with attrition rates roughly 3% higher than than the national average.

Teacher shortages disproportionately impact students experiencing poverty. The Hechinger Report states, “Shortages were concentrated in low-income schools and certain specialties. Wealthy suburban schools might have dozens of applicants for an elementary school teacher, while schools in poor urban neighborhoods and remote rural areas might struggle to find certified teachers in special education or in teaching students who are learning English.”

Heather Schwartz from RAND found “77 percent of schools went on a hiring spree in 2021-22 as $190 billion in federal pandemic funds started flowing.” The RAND report notes that schools and states have used the federal funds to increase staffing, focused on increasing the number of tutoring and substitute teacher roles previously available. This may have contributed to a misleading narrative around vacant positions; attrition isn’t necessarily running rampant, but there are more positions being created than what existed in schools pre-Pandemic.

This leads to a different conundrum; school system leaders are worried about federal funds running out and the ability to sustain interventions and newly added positions.

Finally, the social emotional health of students and staff remains a concern. Bigger questions exist regarding to what extent long-term mental health supports need to be interwoven into school infrastructure and school budgets.

Back in December, our team at Leanlab Education initiated an emergency needs assessment, sensing apathy and burnout among teachers. In response, we published Tell Us How You Really Feel—a report compiling the sentiment of 242 teachers across diverse classroom settings.

Outside of Covid protocols, top challenges cited:

Student behavior & social - emotional well being

Teacher burnout (Understaffing, exhaustion, workload)

Student learning challenges

Top “Bright Spots” and successes included:

Student relationships and engagement

Teacher collaboration

Teachers’ relationships with students and the thrill of seeing students master new material are keeping the remaining educators in the system. However, they need support. Now.

Another study commissioned by Hall Family Foundation (one of our local funders) and conducted by Bellwether with more than 1700 participants suggests attrition may be at similar levels to prior years. Between the studies there are consistencies; all teachers aren’t necessarily burnt out to the point of leaving, but they do need ways to feel effective and supported in their roles. I can’t help but wonder about the connection between supporting our educators and the need to accelerate student outcomes.

From this data, questions emerge:

What will it take to accelerate gains in learning outcomes, particularly for historically marginalized/underserved student populations?

How is human capital connected to learning outcomes and how might we optimize educator support to accelerate learning?

What role can technology and innovation play in accelerating learning outcomes?

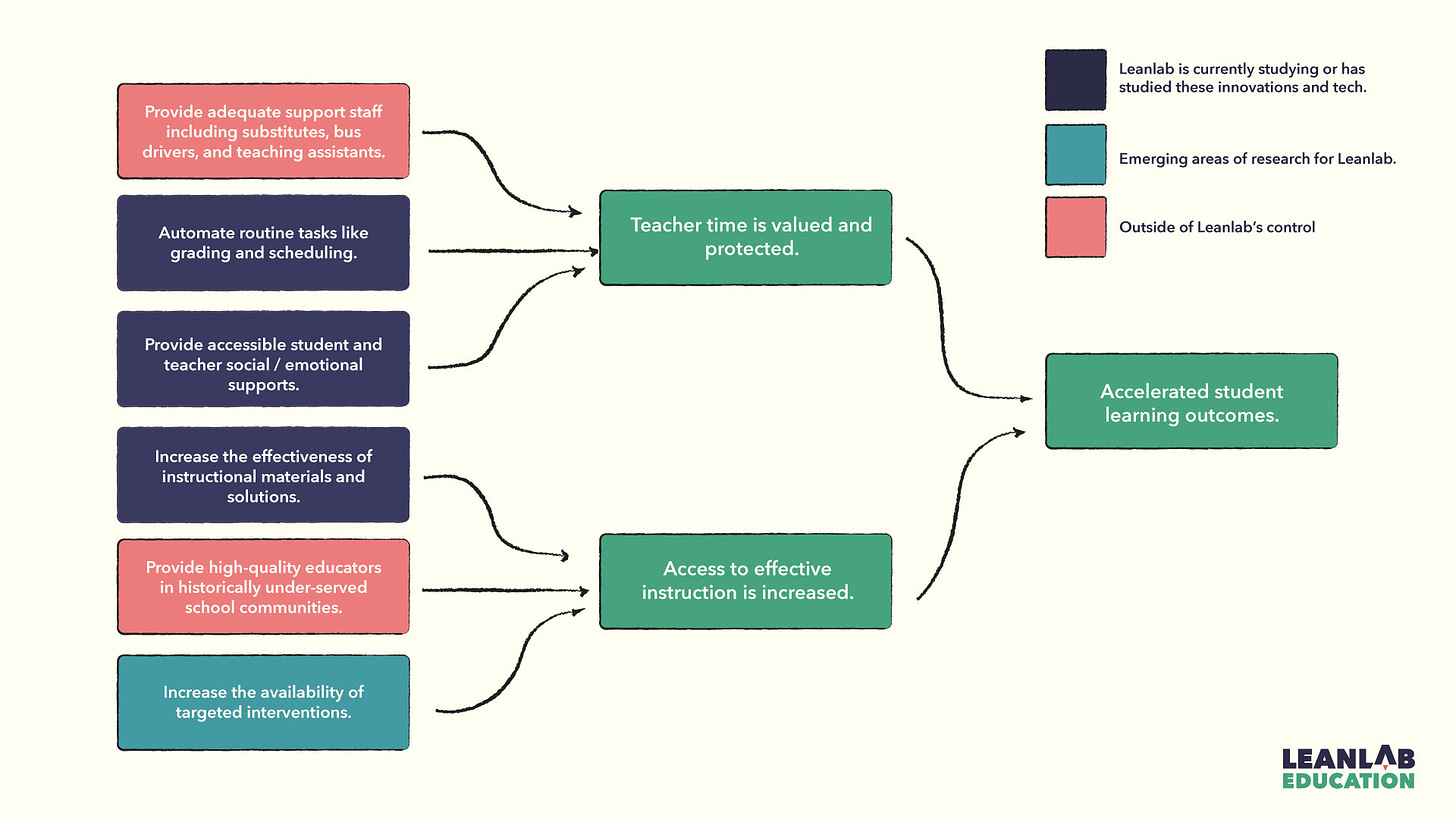

In an attempt to answer such questions, I sketched out a simplified logic model of what a systemic approach to accelerated learning might look like:

Overwhelmingly, our qualitative data tells us that teachers really care. Teachers’ relationships with students and the thrill of seeing students master new material are keeping the remaining educators in the system. However, they need support. Now.

As I read the data, I begin to hypothesize that we can’t accelerate learning without urgently focusing on the teaching experience. We must make teaching more sustainable and more effective. This might be achieved if we focus on two key outputs:

1) Protect teacher and instructional time—at all costs, and

2) Increase access to effective (and by effective, I mean demonstrably evidence-based) instructional tools.

I don’t believe that tech is an end-all panacea for a fundamental human capital problem, but I do think it can be useful lever to streamline processes that have become undesirable or cumbersome for teachers, while also helping us find more efficiencies in a system that’s worried about sustained impact once federal funds dry up.

Within our locus of control at Leanlab Education is how emerging technology products evolve—and how educators and school communities can contribute to their evolution. Personally, I’m curious about how these activities impact the sector—by engaging in innovation, in discovery, in active-problem solving by codesigning and evaluating solutions, can sentiment be shifted? If we extend opportunities to create and meaningfully engage in research to educators, might we be able to slow the burn and refocus the field on learning? Perhaps another logic model emerges.